Pregnant ladies wielding swords and carrying martial helmets, fetuses set to avenge their fathers—and a harsh world the place not all newborns have been born free or given burial.

These are a number of the realities uncovered by the primary interdisciplinary research to give attention to being pregnant within the Viking age, authored on my own, Kate Olley, Brad Marshall and Emma Tollefsen as a part of the Physique-Politics undertaking. Regardless of its central function in human historical past, being pregnant has typically been neglected in archaeology, largely as a result of it leaves little materials hint.

Being pregnant has maybe been significantly neglected in durations we largely affiliate with warriors, kings and battles—reminiscent of the extremely romanticised Viking age (the interval from AD800 till AD1050).

Matters reminiscent of being pregnant and childbirth have conventionally been seen as “ladies’s points”, belonging to the “pure” or “personal” spheres—but we argue that questions reminiscent of “when does life start?” are by no means pure or personal, however of great political concern, at the moment as prior to now.

In our new research, my co-authors and I puzzle collectively eclectic strands of proof as a way to perceive how being pregnant and the pregnant physique have been conceptualized right now. By exploring such “womb politics”, it’s doable so as to add considerably to our information on gender, our bodies and sexual politics within the Viking age and past.

First, we examined phrases and tales depicting being pregnant in Outdated Norse sources. Regardless of courting to the centuries after the Viking age, sagas and authorized texts present phrases and tales about childbearing that the Vikings’ fast descendants used and circulated.

We realized that being pregnant might be described as “bellyful”, “unlight” and “not entire”. And we gleaned an perception into the doable perception in personhood of a fetus: “A lady strolling not alone.”

Wiki Commons

An episode in one of many sagas we checked out helps the concept that unborn youngsters (a minimum of high-status ones) might already be inscribed into advanced techniques of kinship, allies, feuds and obligations. It tells the story of a tense confrontation between the pregnant Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir, a protagonist within the Saga of the Folks of Laxardal and her husband’s killer, Helgi Harðbeinsson.

As a provocation, Helgi wipes his bloody spear on Guđrun’s garments and over her stomach. He declares: “I feel that underneath the nook of that scarf dwells my very own dying.” Helgi’s prediction comes true, and the fetus grows as much as avenge his father.

One other episode, from the Saga of Erik the Purple, focuses extra on the company of the mom. The closely pregnant Freydís Eiríksdóttir is caught up in an assault by the skrælings, the Norse title for the indigenous populations of Greenland and Canada. When she can not escape attributable to her being pregnant, Freydís picks up a sword, bares her breast and strikes the sword towards it, scaring the assailants away.

Whereas generally considered an obscure literary episode in scholarship, this story might discover a parallel within the second set of proof we examined for the research: a figurine of a pregnant lady.

This pendant, present in a tenth-century lady’s burial in Aska, Sweden, is the one recognized convincing depiction of being pregnant from the Viking age. It depicts a determine in feminine gown with the arms embracing an accentuated stomach—maybe signaling reference to the approaching youngster. What makes this figurine particularly attention-grabbing is that the pregnant lady is carrying a martial helmet.

Historiska Museet, CC BY-ND

Taken collectively, these strands of proof present that pregnant ladies might, a minimum of in artwork and tales, be engaged with violence and weapons. These weren’t passive our bodies. Along with latest research of Viking ladies buried as warriors, this provokes additional thought to how we envisage gender roles within the oft-perceived hyper-masculine Viking societies.

Lacking youngsters and being pregnant as a defect

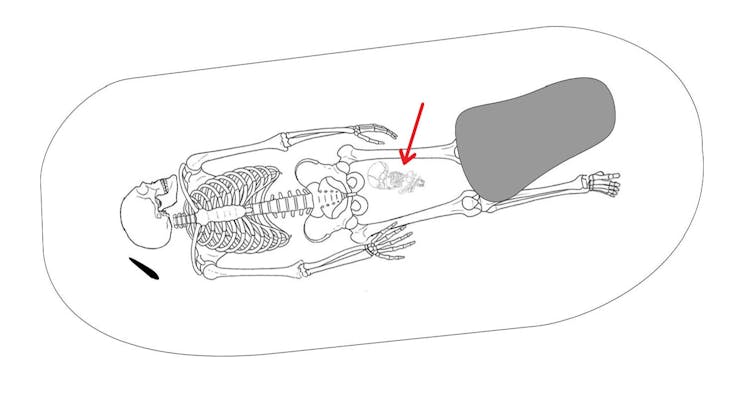

A last strand of investigation was to search for proof for obstetric deaths within the Viking burial document. Maternal-infant dying charges are considered very excessive in most pre-industrial societies. But, we discovered that amongst 1000’s of Viking graves, solely 14 doable mother-infant burials are reported.

Consequently, we advise that pregnant ladies who died weren’t routinely buried with their unborn youngster and should not have been commemorated as one, symbiotic unity by Viking societies. In reality, we additionally discovered newborns buried with grownup males and postmenopausal ladies, assemblages which can be household graves, however they could even be one thing else altogether.

Matt Hitchcock / Physique-Politics, CC BY-SA

We can not exclude that infants—underrepresented within the burial document extra typically—have been disposed of in dying elsewhere. When they’re present in graves with different our bodies, it’s doable they have been included as a “grave good” (objects buried with a deceased particular person) for different folks within the grave.

It is a stark reminder that being pregnant and infancy might be weak states of transition. A last piece of proof speaks so far like no different. For some, like Guđrun’s little boy, gestation and delivery represented a multi-staged course of in the direction of changing into a free social particular person.

For folks decrease on the social rung, nevertheless, this will likely have appeared very completely different. One of many authorized texts we examined dryly informs us that when enslaved ladies have been put up on the market, being pregnant was considered a defect of their our bodies.

Being pregnant was deeply political and much from uniform in which means for Viking-age communities. It formed—and was formed by—concepts of social standing, kinship and personhood. Our research reveals that being pregnant was not invisible or personal, however essential to how Viking societies understood life, social identities and energy.

Marianne Hem Eriksen is an affiliate professor of archaeology on the College of Leicester. This text is republished from The Dialog underneath a Artistic Commons license. Learn the unique article.

![]()